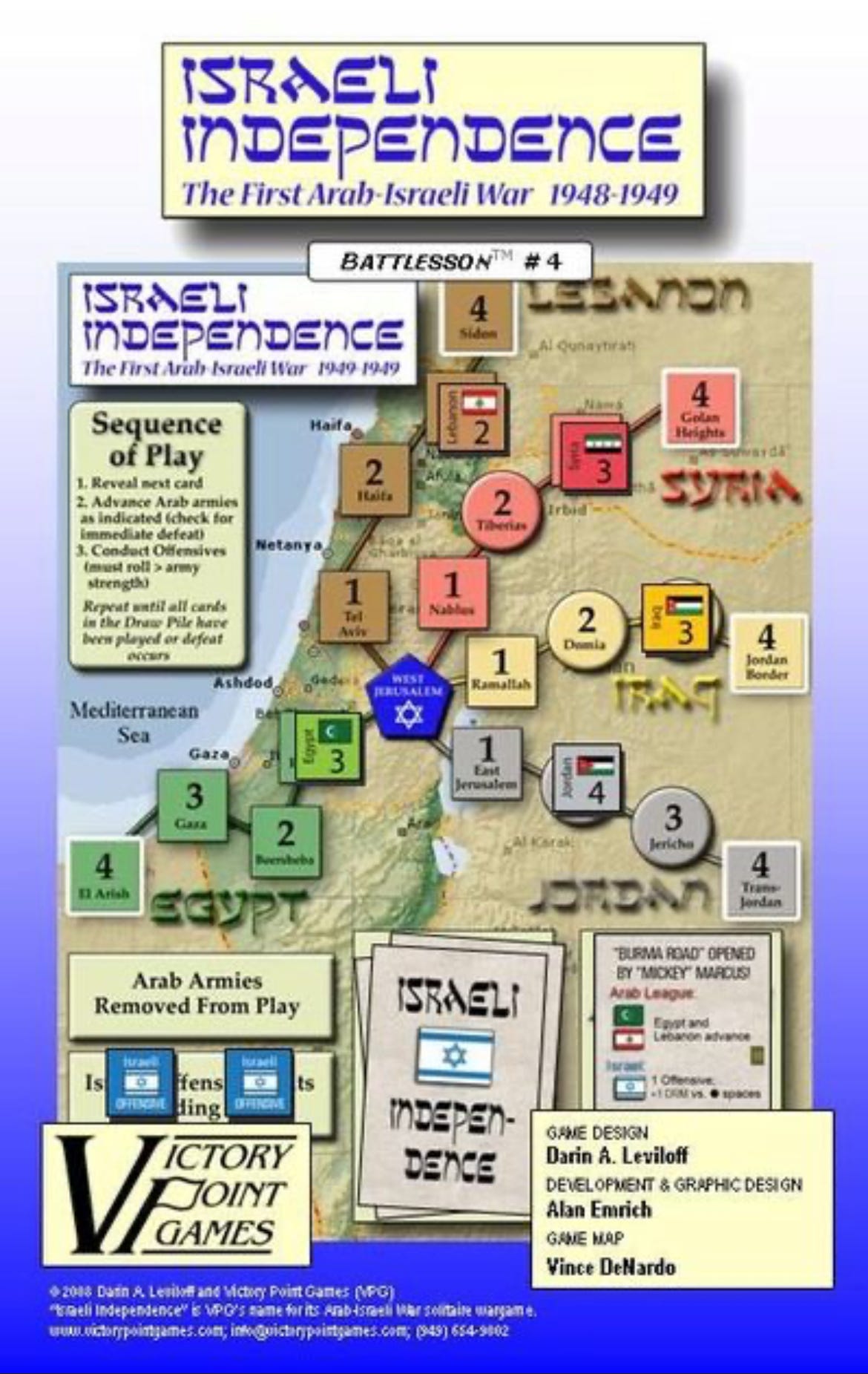

By sheer happenstance, I was fortunate to be there from the very beginning when States of Siege got their start in 2008. I’d just gotten on BGG and come across this small company near where I lived called Victory Point Games. The description for Israeli Independence noted it had only 8 pieces!? It was also a short solo game. With three young children and effectively no time for gaming, I was intrigued and promptly ordered a copy.

Israeli Independence is indeed a very modest game. Yes, there are only eight counters — one for each of five Arab fronts advancing on Jerusalem and three resource markers. The small gameboard has the now iconic tracks radiating from a central point. There is a single two-sided rules sheet, 24 event cards and the smallest die I’d ever seen. A mysteriously conceived ‘expansion’ kit adds 12 extra event cards. I ordered it because I couldn’t see any reason not to. The design has all the core elements of a States of Siege game.

As a small game, it obviously has a limited scope. Yet, it succeeds as fun in a gentle way. Taking only 10-15 minutes, it creates the dilemma of States of Siege: limited resources and multiple threats. Personally, I think of Israeli Independence as more of a proof-of-concept than mature game. It planted the seed for a family of States of Siege games. It was a charming beginning.

Interestingly, for such a small design, ten reviews were written on BGG. That is definitely punching above its weight. But, those reviews also contained the gist of complaints and, I would say, misunderstandings of the States of Siege paradigm that persist to this day.

No Decisions

One of the most common initial reactions when encountering a States of Siege game is to dismiss it:

“There are no meaningful decisions to make.”

“There are no interesting board states to brood over.”

“No strategic decisions.”

I suspect the reason for this conclusion is an SoS game doesn’t fit into the reviewers preconceived notions of what a game ought to be. More traditional games might put players in the role of a commander on a battlefield or of a nation. Directing and maneuvering one’s troops and resources is much more visceral. Bridging the abstraction of game mechanics is straightforward. In a States of Siege game, the level of abstraction is much higher. Effectively, the player’s key roles are twofold: assessing threats and allocating resources.

When encountering this commentary, I will often share information contradicting this. Recently, a reviewer dismissed Soviet Dawn for this reason. When I pointed out the decisions the player must consider, the response of the critic was not gratitude for learning something new. Rather, he was an bit irritated. I imagined him pounding his fist proclaiming: “I am a busy man! I don’t want to spend time and energy figuring out details like this!”

A classic example comes from Soviet Dawn, wherein I point out the plethora of decisions confronting the player right away in the Twilight Deck alone.

Build-up sufficient Legitimacy to prevent Political Collapse.

Acquire some Reorganization markers to survive the Darkness events.

Executing the Tsar.

Dealing with the Czech Legion.

Managing the Finns and Mannerheim.

Sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk or chose the Bukharin Option?

These issues must be balanced successfully to simply survive and make it into later the Darkness and Dawn events; let alone even hope for victory.

Another example would be Resources in The Lost Cause. There are two types of resources in the game—ground and naval. Both types have various permutations for different purposes. Moreover, some of the resources are one-time use. The player has a bunch of choices:

Since the Ground and Naval Resources are separated, do they prioritize one type over the other?

Do they hold one-time resources or do they burn through them quickly?

Is there any reason to not use resources? (Hint: yes.)

Clearly, these limited examples demonstrate the criticism is inaccurate and most likely rooted in ignorance. I could easily provide more.

Obvious Decisions

Another criticism leveled at States of Siege games is the nature of decisions. Critics admit there are decisions to make, but contend they are obvious.

“Attack the closest enemy.”

“You are simply reacting.”

“Whack-a-mole”

If a player is merely attacking the closest enemy front each turn, they are going to lose. Each turn, with rare exceptions, the player typically receives 1-4 Actions. Furthermore, they have a variety of options about how to allocate those actions each turn. Attacking enemy fronts consumes the majority of a player’s actions. However, the devil is in the details.

The closest enemy isn’t necessarily the most dangerous enemy. It could be. If said enemy is at your doorstep and one more advance will see you defeated, absolutely, you must attack that enemy front.

In the game A Blood-Red Banner: The Alamo, the most powerful Mexican unit is the Reserve. With a beefy 4-strength, it is harder to drive it back compared to other Mexican units that are slightly weaker. With multiple enemies advancing, it is actually more productive to initially direct your fire again those weaker units and keep them at bay. This way it is easier to concentrate your fire on the Reserve alone without other units presenting an existential danger.

Similarly, in Hapsburg Eclipse, the Ethnic Loyalties Track has three different groups: Czechs, Croats, Hungarians. The Czechs are the most inclined to rebellion as rated at 4. Whereas, the Hungarians are the most loyal with a rating of 2. The Hungarians are the most easily mollified and kept loyal to the Empire. Because of this, it behooves the player to always focus on them first. Prioritizing ‘easier’ actions is very productive, but to many players counter-intuitive. My point being the most obvious action isn’t always so obvious. Indeed, depending on circumstances, doing the obvious can be a poor choice.

No Agency

The charge of “no agency” is a combination of the previous two points.

“The game plays me. I don’t play the game.”

“It is a complete luck-fest.”

“I’m just going along for the ride.”

“Never won the game.”

The distinction here being this criticism is more of a response of resignation. Unable or unwilling to investigate the game beyond their first impressions, the player decides to play without agency. For instance, a player will allow their decisions to be guided by whatever DRM’s are on the revealed event card. Or they will ignore certain actions because they are more difficult.

Case in point, to have any hope of winning Soviet Dawn, the player must gain Reorganization markers. But, success is difficult and requires persistence. Choosing the more difficult actions is counterintuitive. So, yes, the player is simply going along for a ride. It is important to realize the player is making a decision to abdicate agency.

That said, I do have some sympathy for these criticisms. After many years of gameplay and reflection, it is apparent to me that many of the States of Siege games could have benefited from more development. While working at VPG, I could see first-hand during the development/production process, there was a definite pressure to finish a project and get it out the door. I have also observed this dynamic at other publishers.

Over the years, my ongoing analysis and developing variants makes it clear to me there is an enormous of untapped potential to these designs. The original States of Siege were created in the heady hothouse atmosphere of VPG. For much of its existence, VPG had an insane bi-weekly publishing schedule. After working at VPG, I got to see how the sausage machine worked. I could see with so many projects, there was only so much development time that could be allocated for a project. I would argue that more development effort could have resulted in richer and deeper designs without significantly greater complexity. Perhaps, with more obvious options for agency, these shallow first impressions would not be so prevalent?

Flavor Text

An Event card has some core elements:

Headline

Advance of Enemies

Actions

Occasionally, there is also a one-time event that sees an enemy/resource added/removed or something unique happens that alters the game state. For example, in Ottoman Sunset, there is the whole mini-game to resolve the Royal Navy effort to ‘Force the Narrows’. Typically, each game has its own unique circumstances to warrant these.

One of the upfront design assumptions made by the early VPG States of Siege games was the inclusion of flavor text. This is a more detailed explanation of the Headline and rationale for the advances and actions found on the Event card. I have found the inclusion of flavor text is counter-productive. Let me explain.

With limited space on the card, the inclusion of a paragraph of text consumes a significant amount of this space. This contributes to the clutter of the card layout. Given this text is effectively a one-time use, it doesn’t enhance gameplay. It merely degrades the aesthetics and functionality of the card. Particularly to casual gamers, this text is often off-putting. Its inclusion is unnecessary to gameplay.

In the recent Tabletop Tycoon versions of Ottoman Sunset and Hapsburg Eclipse, the Headline is augmented with a color illustration. This is an effective enhancement. I am surprised there has been no comment this that I am aware of about this graphical presentation decision. However, this improvement comes with a cost. Given the limited space on the Event cards, the font for the flavor text is tiny. Many gamers have commented on this, often with great displeasure. I think this was a mistake. It would have been better to move the flavor text off the Event cards and put it in the rulebook.

The reason why I point this out is because the inclusion of flavor text actually diverts the player from actively engaging in gameplay decisions. Again, it doesn’t materially affect gameplay. Arguably, it helps set the narrative. But, this is not true. Players read it once, if they are inclined. Even for the diligent, it only slows down gameplay. Over the years, I have noted that when a player diligently reads the flavor text, their engagement in gameplay decisions is low or non-existent. The inclusion of flavor text merely reinforces many of the complaints about States of Siege games. Yes, flavor text should be moved off the Event cards for this reason. Even better, the aesthetics of the event cards would be improved.

De Gustibus

Finally, critics of States of Siege games have a litany of residual complaints. “The game is too simple. Too abstract.” Given the design constraints and assumptions of scale and time frame — most SoS games clock in under an hour — simplicity and abstraction aren’t deficiencies, but necessary virtues. As one reviewer memorably described Israeli Independence as “it ain’t ASL”. For the uninitiated, ASL refers to Advanced Squad Leader. It is notorious for its massive and detailed rulebooks with hundreds of pages. Life has different seasons. Gamers come in a wide assortment of temperaments. States of Siege games are not feasts for the gaming senses and rabbit holes to disappear down. Rather, they are more akin to an everyday meal to be enjoyed frequently. For those seeking a more meaty States of Siege experience, Ben Madison and White Dog Games have been hatching heartier games for those so inclined.

Said reviewer, after noting “it ain’t ASL”, offered a generous sentiment on the diversity of reactions to States of Siege games — de gustibus. This has the virtue of being true and wise. Gamers have all sorts of tastes and temperaments. For those seeking a sublime and efficient gaming experience, States of Siege games are an absolute joy. Meantime, I will continue to patiently explain and gently evangelize the virtues of SoS games to the curmudgeons, the malcontents, the blowhards et al, and, perhaps, lead them to the promised land.

... the flavor of these criticisms is the frequent review that SOS games involve too much dice rolling. One of the reasons I love the SOS series generally is that I love the history itself, and find a "flash card-like" experience to be both immersive and also quite different from other wargames; for example, I like "Kaiserkrieg," but to me it misses the flash-card like experience of Soviet Dawn, Hapsburg Eclipse, MaltaBeseiged and Ottoman Sunset. To me, the thing that elevates a great SOS game above the others is the uniqueness/variability of its gameplay; the different game play variation mechanisms (red army reoganization, Mackensen tiles, radio intercepts, etc.) both have a strong historical tie and yet make the game more complex than simply rolling dice and drawing cards. For some reason, although I love the french revolution from a history perspective, I really don't like Levee en Masse, as I find the historical narrative poorly correlated with the track advances, I find the political tracks too overplayed and too easy to manipulate, and I don't like that the game implicitly suggests disdain for the real historical outcome (Napolean rising to power). Irrespective of one's view, SOS games are clearly about the actual history itself and not so much about the fact that one is playing a game with random outcomes.

I don't have the great enthusiasm for the States of Siege games that you have, but I truly appreciate the in-depth analysis you offer your readers--both on the games themselves, and (in this case) the gamers and critics.